Boeing, Nike, and McDonald's: Why CEO turnover spiked in 2019

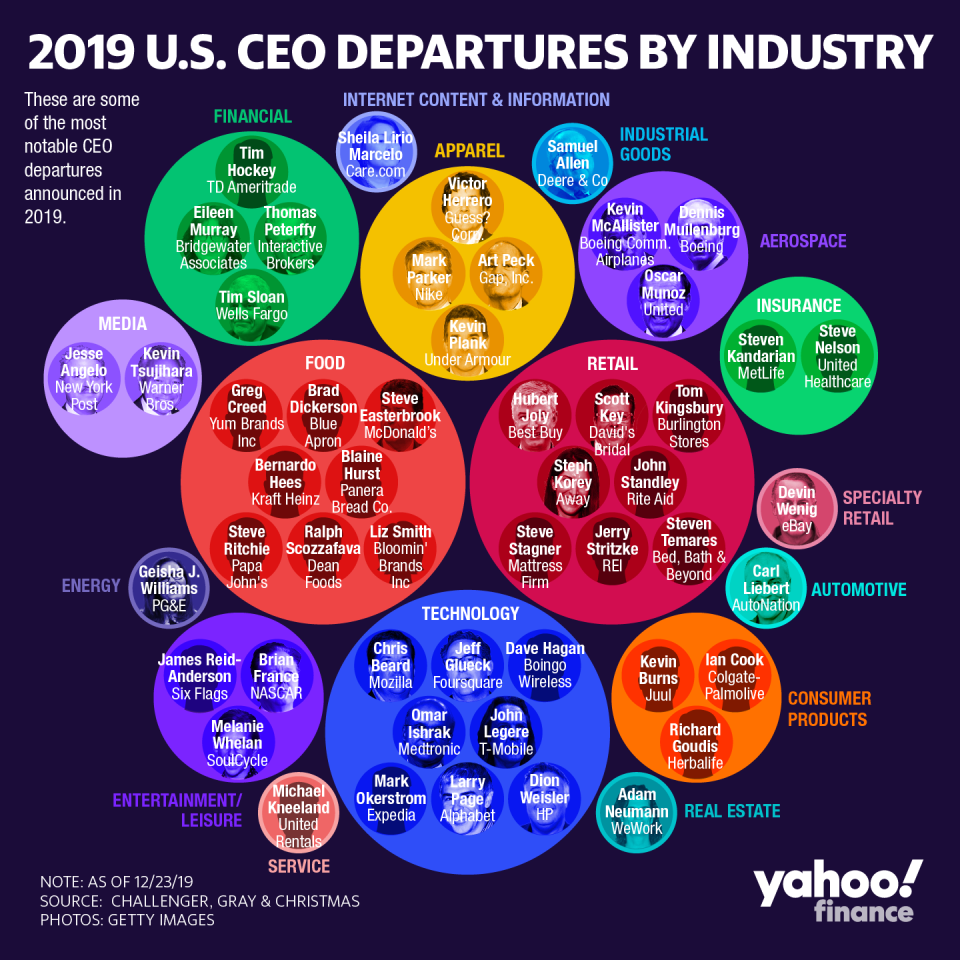

The year 2019 could be called the year of the CEO exodus, with the latest departure being Boeing (BA) CEO Dennis Muilenburg, whose resignation came after two deadly plane crashes.

In 2019 so far, 1,480 chief executives at U.S. companies with at least 10 employees that have been open for at least two years have left their posts, according to a report out on Dec. 11 from the outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

That’s the highest January-November total of CEO exits since the firm began tracking CEO exits in 2002, and it’s hardly surprising to anybody who’s been paying attention.

It seems like every week there’s another high-profile CEO exit — from Nike (NKE) to WeWork to the C-suite shakeup at Expedia (EXPE) and CEO departures at United Airlines (UAL) and Foursquare. This month, the CEO of Away stepped down following a report from The Verge alleging the direct-to-consumer luggage company has a toxic culture. And on Monday, Dec. 23, Boeing announced that Muilenburg had stepped down following months of scrutiny over two crashes of the 737 Max that killed a total of 346 people.

Other major exits this year include Under Armour’s (UA) Kevin Plank, Boeing Commercial Airplanes’ (BA) Kevin McAllister, and Melanie Whelan, the CEO of SoulCycle, whose company has faced competition from newly public at-home exercise company Peloton (PTON).

The list goes on. This year saw an extraordinary number of CEO exits — retirements, forced resignations, ousters — but CEO turnover was on the rise before this year.

A PwC analysis of the world’s largest 2,500 public companies found that CEO turnover hit a then-record high in 2018. And a report last year from the executive data firm Equilar found CEO turnover has shortened the median tenure of CEOs at S&P 500 companies; the median tenure of CEOs at large-cap companies was 6 years in 2013 but had fallen to five years since 2017.

What’s behind this sea change? Experts attribute it to a combination of factors, including the rise of activist investors pushing for a shift in direction at public companies. Moreover, the public has new, more stringent expectations for CEOs’ behavior. Behavior that might have been acceptable in decades past — like dating a subordinate — won’t fly today, especially in the wake of the #MeToo Movement.

“What’s acceptable behavior and what’s not acceptable behavior has changed enormously,” Margarethe Wiersema, a professor at the business school at the University of California, Irvine, told Yahoo Finance. “The expectations have shifted. What you might call the norms of behavior have shifted.”

‘Not above judgment on their personal life’

There is data to back up the observation that CEOs’ ethical lapses are driving turnover. In May of this year, the PwC study of the world’s biggest 2,500 public companies found that the overall rate of forced CEO turnovers was about 20% in 2018 — roughly in line with previous years. But for the first time in the study’s 19-year history, more CEOs were dismissed for ethical lapses than for poor financial performance or issues with the board.

While it’s not always easy to discern reasons for a dismissal, last year and this year saw some notable CEOs whose ouster resulted from an ethical issue unrelated to a company’s performance.

In 2018, Les Moonves stepped down from CBS after a dozen women accused him of sexual misconduct. That departure came after Martin Sorrell, the CEO of ad giant WPP, stepped down amid an investigation into non-specific allegations of personal misconduct. And in November of this year, McDonald’s (MCD) CEO Steve Easterbrook was forced out over “poor judgment involving a recent consensual relationship with an employee.” The CEO of outdoor retailer REI also stepped down this year over a consensual relationship, reportedly because it posed an apparent conflict of interest.

As Wiersema, the University of California, Irvine, professor noted, the #MeToo movement has shown that CEOs are “not above judgment on their personal life, even though it may have been a completely consensual relationship.”

‘I was not on the same page as my new board’

CEOs do not just have to contend with the public judging their behavior, though. These days, they also have to battle with so-called activist investors — people or groups who buy up a sizable number of a company’s shares to obtain board seats.

The last decade has seen a spike in shareholder activism, according to Wiersema, who pointed out that hedge funds have more money these days from institutional investors to pour into activist campaigns. Last year was a record-breaking year for shareholder activism, according to a January 2019 report from Lazard.

Activists targeted 228 companies in 2018 compared to 188 the year before, the Lazard analysis found. These activists won 161 board seats. In fact, 52% of all board seats secured globally between 2013 and 2018 are held by a group of 11 activists, according to analysis from law firm Sullivan & Cromwell.

“There’s more activist directors now coming on board, calling for change,” noted William Klepper, a professor of management at Columbia Business School.

The past decade has seen high-profile CEO firings or resignations amid activist pressure.

In 2017, Arconic CEO Klaus Kleinfeld was jettisoned after he showed “poor judgment” for writing a letter to activist hedge fund Elliott Management without permission from his board. The same year, longtime GE CEO Jeff Immelt resigned while facing pressure from activist investor Trian Fund Management. More recently, this year, Liz Smith, the CEO of Outback Steakhouse parent Bloomin’ Brands, left following pressure from activists who questioned her strategy.

And in September, eBay’s Devin Wenig was open about his reason for departing the company after activist investors Elliott Management and Starboard Value obtained seats on its board.

In the past few weeks it became clear that I was not on the same page as my new Board. Whenever that happens, its best for everyone to turn that page over. It has been an incredible privilege to lead one of the worlds great businesses for the past 8 years.

— Devin Wenig (@devinwenig) September 25, 2019

For some CEOs, negotiating with activist board members simply isn’t worth the trouble, according to Klepper, the Columbia Business School professor, whose books include “The CEO’s boss: Tough love in the boardroom.” “A lot of CEOs are saying, ‘I just don’t need this,’” he said.

But activist investors have led to more forced than voluntary exits, says Wiersema, the University of California, Irvine, professor. “I think that what has happened is that the boards are trying to satisfy the activists,” she said, “and one easy way to satisfy the activists is to get rid of the CEO.”

‘Another opportunity around the corner’

Still, the majority of CEOs — 1,020 out of 1,480 departures this year — left of their own accord, with some retiring and others moving on to another company. More CEOs might have departed this year because the economy has been doing well and they were confident they’d find another top job.

“Quits are probably going up not just for CEOs but for employees in general,” says Joseph Porac, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business. “There is always going to be another opportunity around the corner for them.”

CEOs could also be jumping ship in anticipation of a downturn. “CEO compensation nowadays ... is mainly in the form of some kind of restricted stock, and the stock market has been doing really well,” Porac said. “So there might be a lot of cashing out and moving on.”

If that’s the case, then more CEOs may end up sticking around longer if the economy goes south — that is, if activist investors don’t urge their boards to show them the door.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on Dec. 11 and updated with the news of Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg’s resignation.

Erin Fuchs is deputy managing editor at Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

Target is the Yahoo Finance 2019 Company of the Year

The best movies and TV shows about business we watched in 2019

20 businesses that died in the 2010s

The biggest deals and attempted deals of the 2010s

The stock market's biggest winners and losers of the past decade

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.