How gas stations and Facebook's Libra pushed the Fed to build a new payments system

If you’re an employee looking for a paycheck to hit your checking account or a supplier waiting for pay from the last delivery of goods to a grocery store, you’re probably familiar with the three- to five-day waiting period for a payment to clear.

In the era of electric cars and meatless meat, why is there no instant payment processing person-to-person, person-to-business, or business-to-business?

Enter: the race to build a real-time payments network. Private market players like The Clearing House are trying to revamp bank-to-bank transfers while fintech companies like PayPal’s (PYPL) Venmo offer instant peer-to-peer fund transfers. Then there’s the Libra project, Facebook’s (FB) effort to create a digital currency that would facilitate instant payments on a blockchain.

The latest player to throw its hat into the ring: the Federal Reserve, which announced plans last week to launch its own real-time payments system, FedNow, by 2023 or 2024.

“[O]ne thing is clear: consumers and businesses across the country want and expect real-time payments, and the banks they trust should be able to provide this service securely — whatever their size,” Fed Governor Lael Brainard said August 5, while unveiling plans for FedNow.

The Fed, which usually interfaces the most with the banking industry, found an unusual cheerleader in its proposal to build a real-time payments system: the gas station lobby.

While some express concern over the ability of private players to compete with the Fed, gas stations say the central bank is long overdue on building an accessible and reliable utility that would reduce friction in the payments system.

A pair of kicks

Mike Fortson’s cousin wanted to hook him up with a pair of all-white Nike Vapormaxes, retail price $190, as a gift. The plan: send the money by PayPal so he could deposit the money at his bank and then withdraw the cash for the kicks.

But then PayPal said Fortson had to wait three to five days for the money to be available. He reached out to PayPal but a representative said “there was nothing really they could do.”

“It’s ridiculous,” Fortson told Yahoo Finance, noting that he ultimately turned to Square’s Cash App (SQ) to transfer the money.

PayPal was mostly true in defending its three- to five-day waiting period, which is also standard in bank-to-bank transfers. That’s because the current infrastructure involves a middleman that few consumer know about: the clearinghouse.

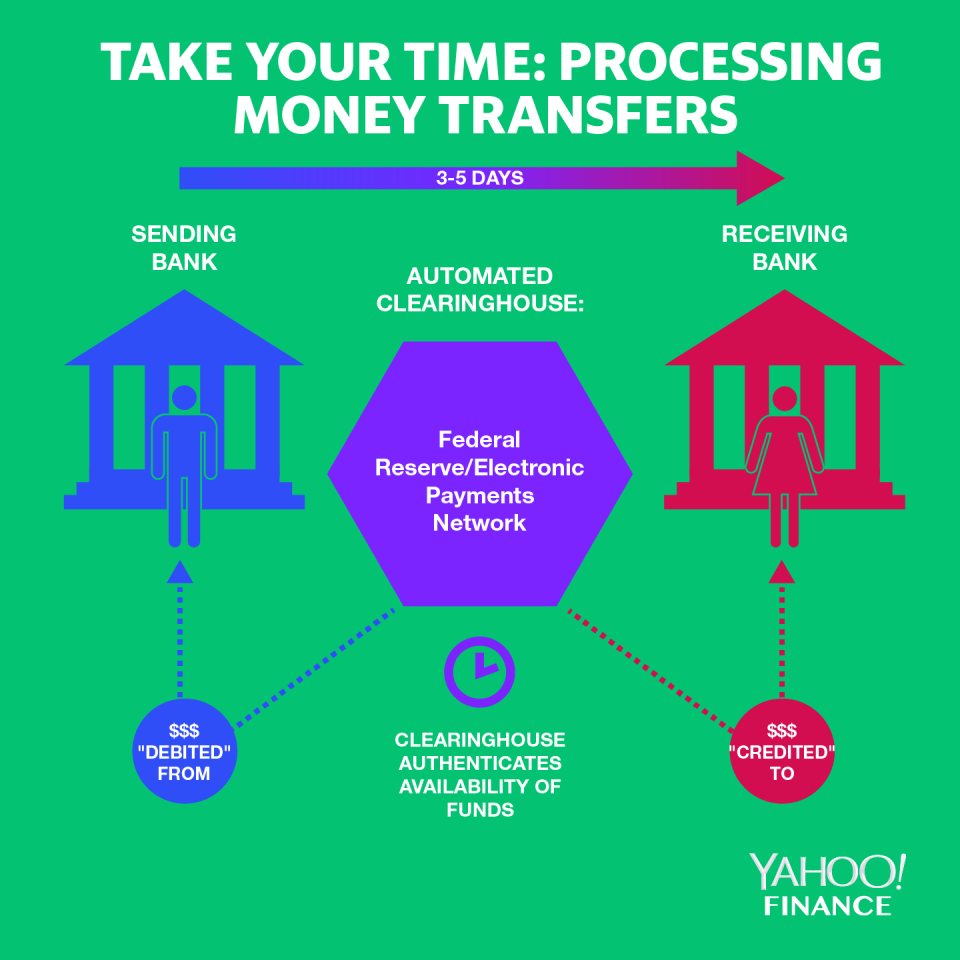

Let’s consider a person trying to pay their monthly $800 rent through an online portal where they’ve linked their bank account for payments. When the tenant authorizes the bank to send the rent money to the landlord, the landlord’s bank will request $800 from the tenant’s bank. The tenant’s bank then debits the tenant for the funds requested and sends the data to an automated clearinghouse (ACH) that is currently operated by the Federal Reserve and the Electronic Payments Network.

The ACH verifies that the tenant has the funds available and then sends the information to the landlord’s bank, which credits the $800 to its account.

The problem: ACH processes transfers in batches only three times a day and does not operate during bank holidays or weekends.

For Mike Fortson, not being able to access funds meant waiting a little longer on those Vapormaxes, but for people who live paycheck-to-paycheck, lacking access to more immediate payment methods can mean turning to temporary solutions like payday loans with dangerously high interest rates.

Businesses aren’t happy, either. At gas stations, people cashing checks to fill up their car for the week, unaware of the arcane mechanics behind the U.S. payments system, will take their wrath out on the gas stations themselves.

“Sometimes they take that frustration out on the local retailer they’re dealing with,” said Doug Kantor, counsel to the National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS) and the Society of Independent Gasoline Marketers of America (SIGMA).

Anything but Kwik

Retailers face issues on the business-to-business side, as well.

Take a convenience store placing an order for a fresh few shelves’ worth of candy on a Friday. Even if the supplier receives the check in-person on the same day and heads to the bank to cash it, the ACH payment would not process for at least two days (Saturday and Sunday) or even three (if Monday is a bank holiday).

To cover the risk of the payment not clearing, the supplier may price a premium to the order price, forcing the store to pay extra for a system out of its control.

Dave Wagner, controller for Wisconsin-based Kwik Trip convenience stores, told Yahoo Finance that a real-time payments system would allow retailers to get a “little bit more on discounts” because the supplier would know they could get their money sooner.

“It helps them on their balance sheet, it helps us out because then we’ve negotiated a little bit of a better deal,” Wagner said. “It kind of works hand-in-hand, you can move that quicker.”

Wagner said the payments issue bleeds into nearly every other B2B transaction as well, from paying plumbers to electricians. It also affects the timeliness of paychecks reaching Kwik Trip employees, who need to receive the money by mail, cash it at a bank, and then wait for the funds to hit their account.

Kwik Trip wrote to the Fed in favor of building its own real-time payments system when the Fed first proposed it last year, accusing private companies of charging “anticompetitive” prices for real-time services.

The Clearing House has offered a real-time payments system for about two years now, and says it serves over 51% of demand deposit accounts in the country.

Steve Ledford, a spokesperson for TCH, told Yahoo Finance that he is “not a fan” of a government entity offering its own service.

“When it comes down to it, the private sector is better off coming up with innovative solutions,” Ledford said.

Among the concerns with the Fed entering the ring: a multiplicity of payment systems that may not interact well with one another and Fed pricing that could undercut private market offerings.

Taking on Libra

Fintech firms have proposed alternatives for consumers trying to send money to other consumers.

Venmo, for example, allows a consumer to send money from one wallet (linked to a bank account or debit card) to another person’s wallet instantly. Venmo now has a debit card backed by funds in a user’s Venmo account, allowing the user to instantly spend that money at merchants accepting Mastercard.

But regardless of what fintech wallet you’re using (Venmo, Cash App, or PayPal), once you try to send funds from the app to your checking account, the money has to clear the ACH system and gets caught up in the dreaded three- to five-day limbo.

The most attention-grabbing proposal as of late has been Facebook’s, which proposes a “Calibra” digital wallet in which users would store units of Libra (after converting their local currency). Libra would operate on its own blockchain and would involve participation from 28 founding members including payment processors like Mastercard (MA) and Visa (V) in addition to service providers like Lyft (LYFT) and Spotify (SPOT).

One proposed use case for Libra would be easily transferring money across international jurisdictions.

The Fed faced pressure on Capitol Hill shortly after the Libra project was announced, and Chairman Jerome Powell insisted that it “cannot go forward” without addressing concerns on money laundering, data protection, and consumer privacy.

But while unveiling FedNow, Brainard acknowledged that the Libra project is one effort to “establish a payment system that bypasses our banks and our currency.”

Although FedNow does not propose to address many of Libra’s use cases, faster payments could encourage more Americans to stick with bank-to-bank payment systems instead of hoarding money in Libra.

Calibra declined to comment. Visa also declined to comment for the story, and Mastercard did not respond to requests for comment. PayPal and Square also did not respond to comment for this story.

In the payments race, the winner may be the player who can get to market the quickest. Libra hopes to launch next year but could be delayed by regulatory issues.

Aaron Klein, a fellow at the Brookings Institute, said the longer the Fed waits, the more the U.S. lags behind countries that already have real-time payments systems.

“I’m apoplectic that the Fed won’t mandate check clearing technology that the rest of the world has enjoyed for over 10 years,” Klein said.

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the banking industry and the intersection of finance and policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

The grey area between currency devaluation and currency manipulation

Boston Fed President: No 'clear and compelling' case for this week's rate cut

Congress may have accidentally freed nearly all banks from the Volcker Rule

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance