Research details the 'rapid increase in homelessness' in certain U.S. cities

Across some of the biggest U.S. cities, rent prices are continuing to rise for lower-income Americans. Meanwhile, an estimated 553,000 people experienced homelessness in 2018, according to Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) data.

And a recent Zillow study — which estimated the number of homeless people in America to be closer to 661,000 — found a specific correlation between rent affordability and the rate of homelessness at a certain threshold: “Communities where people spend more than 32 percent of their income on rent can expect a more rapid increase in homelessness.”

Alexander Casey, a policy advisor on Zillow’s Economic Research team, explained to Yahoo Finance that “15% of the U.S. population lives in areas where a staggering 47% of the homeless population lives. And these are areas where rents are 29% higher on average than the rest of the U.S. And most of these communities are already past this 32% tipping point.”

New York City, Los Angeles, and Seattle stand apart

Zillow researchers clustered different communities together based on “how they’re experiencing rising poverty rates, existing homelessness, homelessness rates, and declining affordability.” The places where people are most at risk of homelessness, according to the study, included New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Boston, “which all have crossed the 32 percent affordability threshold.”

The three U.S. cities with the most homeless people in 2018 were New York (78,676), Los Angeles (49,955), and Seattle (12,112), according to the most recent HUD data. A 2016 Wall Street Journal report highlighted that while overall homelessness in America was declining, the homeless population in these cities and others had risen rapidly since 2010.

“We attribute a great majority of homelessness to rent affordability,” Megan Hustings, interim director of the National Coalition for the Homeless, told Yahoo Finance. She added that gentrification plays a big role in it, along with public housing developments in urban areas being torn down and the overall “continuous decline of affordable housing units.”

In June 2018, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) received widespread criticism after an Associated Press analysis found that a proposed HUD plan would raise the rent of low-income tenants by about 20%. (Due to the ongoing government shutdown, HUD could not be reached for comment about public housing developments.)

High rent in America is a fact of life these days

“We’ve seen rent rising,” Casey said. “Why is that? Can we disentangle that? You start to realize the story of rent affordability and homelessness doesn’t read the same in every single community.”

Over the last five years, the U.S. median rent has risen 11%. As a result, renters earning the national median income have spent 28.2% of their earnings on a rental. According to Zillow, that is significantly “above the 17.7% that median-income households buying a typical home today spend on their monthly mortgage payment.”

When rent affordability exceeds 22%, according to the study, that leads to more people in that community experiencing homelessness. And any increase in rent affordability beyond 32% “leads to a faster-rising rate of homelessness — which could mean a homelessness crisis, unless there are mitigating factors within a community,” Zillow reported.

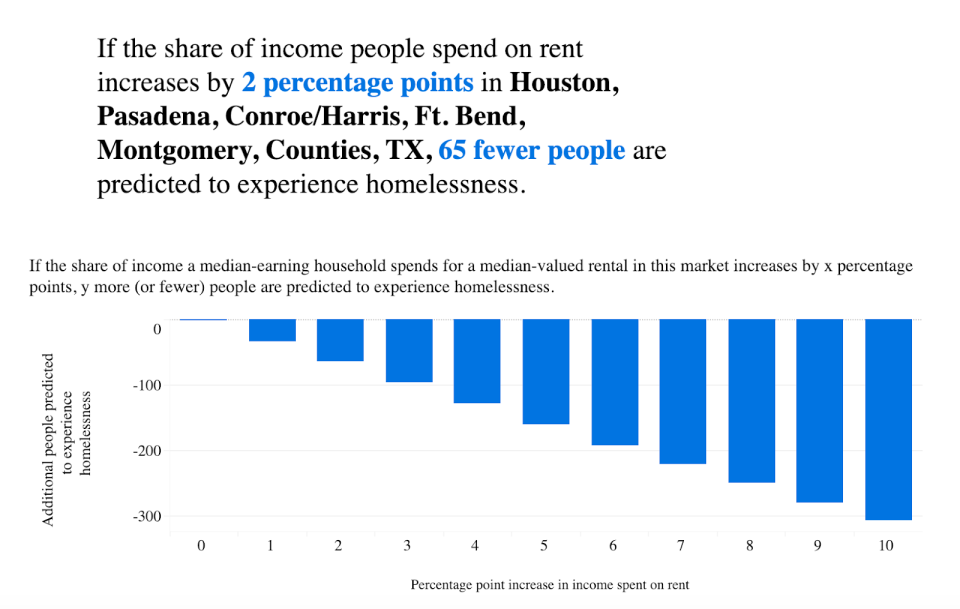

A good example, according to Casey, is in Houston, Texas. The researchers looked at trends in the city’s rising rent prices and chronic high poverty rates.

“You see that homelessness rates are significantly lower to similar peer communities in Houston,” Casey said. “The model helps identify Houston as an example as a place of: ‘Here’s other peer communities where national policy folks might want to start to look to see what lessons can be learned. What kind of policies are they implementing?’”

According to National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC)’s Out of Reach 2018 report, a full-time worker earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 “needs to work approximately 122 hours per week for all 52 weeks of the year, or approximately three full-time jobs, to afford a two-bedroom rental home at the national average fair market rent.”

And, the report stated, in no state “can a worker earning the federal minimum wage or prevailing state minimum wage afford a two-bedroom rental home at fair market rent by working a standard 40-hour week.”

‘The problem is that there’s just so much poverty’

Although it may seem that raising the minimum wage is the solution to fixing this rent affordability issue, Casey argues that may not be the case.

“Los Angeles is a fascinating example,” Casey said. “In L.A., the rent affordability there is really off the charts, no matter how you measure it. Even if you’re a person in L.A. who’s earning the typical income, it’s going to be pretty stretched to afford even a modest-priced rental in that area.

Casey continued: “So what I think L.A. really speaks to is that even if you raised incomes for people that are the most vulnerable to becoming homeless to a significant degree, there just isn’t the availability of housing for them, where you might think in a different city, there are some cheaper rental options available. The problem is that there’s just so much poverty, so few resources, that even if there’s a place that wouldn’t require that much money’s rent every month, that money isn’t there.”

‘The interconnected web of the housing market’

Casey, like Hustings, said that gentrification is a significant factor.

“When we think about gentrification, we think about displacement spillover from one area to the other,” Casey said. “As rent increases that outpaces someone’s income, they’re probably not the people that are going to be experiencing homelessness. They’re just going to rent at a cheaper price.

“But, the fact that data is available at the median and changes for the median income renter are predictive to homelessness rates is just a really powerful illustration of something I think a lot of people fail to recognize,” Casey said, “which is the interconnected web of the housing market. If changes to affordability is affecting someone at the median income level, they might restitute, replace, and bump people down further and further.”

Casey added: “Gentrification is a topic that illustrates how interconnected the rental market is, and that changes to rental prices to one person is kind of a trickle-down effect.”

‘Illustrative for policymakers to bring to Washington’

Casey concluded that there were several key takeaways from the report.

“This research has helped identify that it’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all solution, and that each of these markets are dealing with very different types of problems,” he said. “In one market, there are things that need to be done in terms of increasing the supply of affordable housing because even with income-based subsidies, and even with vouchers or tenant support, there haven’t been the number of units to help house people.”

He continued: “In other places, there might be units available but they’re sub-standard and there needs to be substantial resources put to the rehabilitation of affordable housing stock. In other places, housing might be decently affordable relatively, and it’s a matter of providing vouchers or income subsidies to families. And still, in other places, there are a wide variety of these types of approaches. Flexibility can be implemented in more local solutions.”

As for the future, Casey hoped policymakers used this kind of research to tackle the nuance of the issue.

“This has helped be illustrative for policymakers to bring to Washington to show we might have different problems here than folks over here,” he said, “and we can shape responses accordingly.”

Adriana is an associate editor for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

READ MORE:

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.